Why Read: Devaluing the US dollar serves multiple purposes: combating foreign currency manipulation and dumping and inflating away national debt. But the burgeoning currency war is also risky.

This week, we cover historical contexts for the global economic situation, the state of currencies today, and why President Trump likely wants a cheap dollar. Read on to learn what it means for us as employees, businesspeople, investors, and owners of money.

... [I]t is peculiarly the duty of the national government to secure to the people a sound circulating medium ... furnish[ing] to the people a currency as safe as their own government. - Abraham Lincoln

A currency war between nations is a tit-for-tat policy of official currency devaluation aimed at improving nations' foreign trade competitiveness at the expense of other nations. Currency devaluation is a deliberate move to reduce the purchasing power of a nation's own currency to boost its export sales.

Countries may pursue such a strategy to gain a competitive edge in global trade and reduce their sovereign debt burden. Devaluation can have unintended consequences that are self-defeating; the worst of these is inflation. During a currency war, a nation's consumers also bear the burden of higher prices on imports. - Investopedia

Money, it's a gas. - Pink Floyd, "Money," The Dark Side of the Moon

Throughout history, nations and empires have played an on-and-off game of chicken with their own currencies. At times, this looks like the era of quantitative easing seen after the Global Financial Collapse of 2007/2008, or the COVID-19 pandemic economic response around the world. Firehoses of cash that go pouring into the economy to avoid disaster do, of course, have consequences.

Usually, the contours of those consequences are defined by the eras of high inflation seen immediately afterward. Bubbles appear, economies overheat, and the price of goods for the public becomes nothing short of painful - doubly so if wages don't shift markedly while the money supply does.

There is more to international financial competition, however, than meets the eye.

Setting the Stage

U.S. exports to retaliating countries fell by as much as 33%, with U.S. trade partners specifically targeting high-end, branded consumer products, such as U.S. autos. The drop in trade contributed to the Great Depression, which in turn triggered a large currency war: between 1929 and 1936, 70 countries devalued their currencies relative to gold. We show that trade was further reduced by more than 21% following devaluation. The currency war destroyed the trade-enhancing benefits of the global monetary standard, ending regime coordination and increasing trade costs. The 1930s are a potent reminder of what can happen when international policy coordination breaks down and countries go it alone when negotiating trade and exchange-rate policies. - Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Policy Brief,"Trade Wars and Currency Wars: Lessons from History" (May 2025)

Among the forms of economic warfare available in the toolkit of nations is a proper devaluation of one's own currency for the purpose of outcompeting trade partners. This tactic, seen particularly in Japan in the 1980s and '90s and in China from around 2000 on, works well to siphon manufacturing and production from those targeted, as the cheap goods that result in domestic markets of countries with higher-value currencies outcompete those produced in-country.

But this tactic in our most modern times only worked in such a one-directional fashion because the original currency in the targeted nations (read: the US, the EU) stayed roughly stable and much higher.

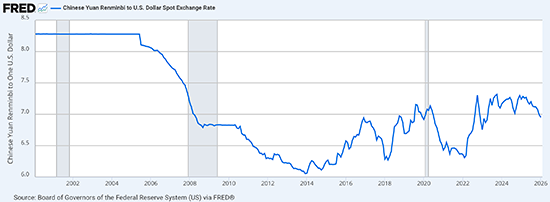

Source: Council on Foreign Relations

The charts above show two eras illustrative of a currency manipulated by a central government. In the top chart, the open pegging of the Chinese yuan by the government of the People's Republic of China (PRC) circa 2000-06, and again during the 2008 financial crisis, are obvious due to the flat lines in the exchange rate. The second chart shows the new approach adopted by PRC officials after the country's accession to the WTO and much complaint from its trading partners worldwide. There was a shift to a daily peg that allowed for some movement but kept the currency within a band that belies the idea that it truly "floated."

But things can get a lot weirder.

The reason this occurred in one-way fashion - emptying out the factories of the United States and Europe and shifting them to China as price competition (and wage competition) invalidated Western production - was that the countries being targeted did, for the most part, follow WTO and international standards. Properly floated (and untethered to gold after the 1970s in the US), the dollar continued on its way, highly valued and dominant in the global economy as the chief reserve currency.

While much has been made of Richard Nixon's abandonment of the gold standard over the years, it remains true that the move (originally to stave off currency issues during the US engagement in Vietnam) was not unique. Until that time, the United States had effectively provided a sole reserve "reality check" currency that had a basis in tethering to the world at large due to the planning of the new global economy heralded by the postwar Bretton Woods Agreement.

But European currencies used to be backed by gold.

That was no longer the case by the time World War II was ramping up. In the post-WWI runup to the Great Depression and throughout the 1930s, the struggling nations of Europe and the United States fought a currency war of epic proportions. The US and France had bolstered the British pound sterling throughout the 1920s. But as the markets crashed in 1929, France, struggling with an anemic economy heavily battered by the horror of the war, began selling off British pounds at a rapid clip.

France and the US began massively hoarding gold. The 1934 Gold Reserve Act in the United States effectively devalued the dollar by switching its "gold content" from $20.67 to $35, nearly halving the amount of gold backing per dollar and flooding the money supply. Paired with Executive Order 6102, which effectively made owning too much gold in America illegal, this allowed the Fed to buy up gold and dump dollars into the economy. Add in the Smoot-Hawley tariffs of 1930, and Britain and France had themselves a real problem.

The British, in turn, dropped the gold standard.

In all the back-and-forth, chaos reigned. All this was finally put to rest in 1936 with the Tripartite Agreement, with the countries informally agreeing to put the conflict to rest because, well, it helped to destroy the international monetary system.

Currency wars can be dangerous.

These days, the People's Bank of China has effectively abandoned even the pretense of market-related floating. In a piece published by the Council on Foreign Relations in April 2024, author Brad Setser noted that:

Faced with ongoing depreciation pressures (and a regime where, absent heavy-handed intervention by the PBOC, the market was basically leading the yuan to crawl down), the PBOC dropped the pretense that the yuan, which is required to trade within a two-percentage point band around the daily fix - was flexible and that the fix was somehow market determined. The fix just stopped moving, which meant that spot could weaken further.

Bang. How's that for a shot heard 'round the world?

Setser goes on to explain that the PRC has simultaneously used production, not monetary stimulus, to flood the global markets with cheap goods in response to COVID, producing far more than the global economy can even take up based on GDP growth numbers. This, while useful in domestic economic stimulus in China, is also textbook economic warfare - and the rates at which it is occurring threaten the entire global economy.

And so we find ourselves, yet again, in a place of danger. The moments of stimulus and QE in 2008-11 were debatably a short currency war. The chaos of the 1930s was the most damning example of such conflict.

The currency war we're facing now is one of truly epic proportions.

The Dollar Goes Down

Unlike the buoyant U.S. stock market, the dollar is sinking fast.

The value of the greenback just hit a four-year low, according to the ICE U.S. Dollar Index, the Intercontinental Exchange's measure of the currency against a basket of six other major currencies. While much of the decline has occurred over the past year, the dollar has slid more than 3% since mid-January, according to the index. - CBS News (2/29/26)

With China returning to more outright currency manipulation while flooding the global market with more goods than it can buy, the next question is the dollar. Since policy and pretense change by administration in the US, let's take a look at that dollar since January 20, 2025, in relation to gold and the other top global currencies. (Note that the euro, pound, and Australian dollar are measured in those currencies against the US dollar and therefore placed first after gold to avoid headache.)

Graphics source: Trading Economics

The dollar's depreciation since Donald Trump's inauguration is pronounced. This is against gold, but so too against every major global currency but the yen. For simplicity's sake, the following are the rough percentage changes, in just over a year, by currency against the USD:

Gold: ~40%

Euro: ~15%

Australian dollar: ~11%

British pound: ~10%

Chinese yuan: ~5%

Canadian dollar: ~5%

Swiss franc: ~15%

Japanese yen: ~-2.5%

The US dollar is moving fast, particularly given its historical context as one of the more stable currencies. The exceptions here, with China and Canada seeing less of a drop and the Japanese yen seeing a slight uptick, are all relatively explicable: China manipulates its currency, Japan's spending is set to rise dramatically under new PM Takaichi, and Canada's currency was battered by the other tit-for-tat going on: brutal tariff fights with the US.

Meanwhile, Europe has tempered its responses and focused on a wait-and-see approach at both the Bank of England and on the continent.

The Cheaper the Better

"No, I think it's great," Trump told reporters in Iowa on Tuesday when asked if he was worried about the currency's drop. "I think the value of the dollar - look at the business we're doing. The dollar's doing great." - Yahoo Finance(1/28/26)

Dollar depreciation leads to higher inflation and ultimately forces foreign creditors to question their rationale and indeed their sanity for continuing purchases of U.S. Treasuries. - Bill Gross, Co-Founder, PIMCO

Much has been made of the depreciation of the dollar being some sort of accident of late. The Yahoo Finance piece quoted above shows the theme seen in global media. The assumption that a falling dollar is somehow weighing on Trump seems nearly universal, at least in public circles. The quote above shows it is not.

But the world is in an economic conflict. Much like in the 1930s, the current atmosphere is one of great powers struggling to emerge from a crisis (the pandemic) and outcompete one another on production and exports. With China in the lead and pouring goods into the market, Trump is actively running a trade war that, apparently, is not going so well in East Asia. Tariffs on Chinese goods were quickly abandoned when the predicted "hammer" fell and Xi Jinping threatened to cut the United States off from rare earth elements.

Letting the dollar fall is another way to skin the cat.

This should come as no surprise. Since the 1980s, Trump has been complaining about the trade deficit and unfair practices being used against the United States. In a 1987 Larry King interview mainly focused on Japan's unfair practices, he repeated his concerns over and over, stating: "I was tired, and I think a lot of people are tired, of watching people rip off the United States." Referring to the trade deficit, he went on to note: "Larry, the country is losing $200 billion dollars a year - $200 billion."

So, tariffs it is. Given that tariffs are just a tax on American citizens once companies pass along the cost, that means price inflation for the American consumer. Consumer Price Index numbers were relatively stable compared with recent pandemic swings, but they remain elevated at 2.6% for the year, and that's the official number under the administration.

Heads turned when it was announced that last October's stats would not be collected because of the government shutdown. This was unprecedented (no other shutdown has stopped the Bureau of Labor Statistics from collecting this data) and conveniently close to the meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which was set to examine and adjust interest rates. (It dropped them by a quarter point.) Now, the data blackout is happening again, just three months later - again ostensibly due to government shutdown.

The part of the trade war that appeared to be "working" was in the monthly numbers, showing a narrowing to $29 billion for the month of November. But month-to-month numbers belie the variations that often occur throughout the year. As of the end of November 2025, the deficit for the 12 months priorstood at $936.45 billion, or a growing deficit compared with 2024 (~$918 billion), and closing in on the highest annual deficit in US history, in 2022(~$960 billion).

Meanwhile, the FOMC meeting in November concluded with a decision to end quantitative tightening starting December 1. This normally would mean that inflation could rise further. All of this was happening at a time when the easing of M1 and M2 money supply, which went up in a flat wall during pandemic bailouts and had finally begun to ease, had started to rise again:

While Trump announced a new Fed chair this year (Kevin Warsh) who is considered hawkish on inflation (likely as a strategy to assuage some of the worry), he remains in a situation where each move he can make on trade will cause inflation at home. And no president has been more aggressive about lambasting the Fed in attempts to get rates cut. The benefits to things like the housing market from Fed rates are minimal, but gushing dollars into the system harms Trump's voting base directly, as it is a de facto tax on their wealth. So, too, are tariffs.

But a depreciated (or devalued - meaning, purposefully) currency serves two key purposes that seem to be mainly ignored in the mainstream discussion. A cheaper US dollar helps combat the Chinese dumping that is currently eating the heart out of manufacturing in other targeted regions. Whether, and how much, this works remains to be seen; but fighting fire with fire does make sense in this context, at least for domestic production.

Meanwhile, the United States has entered the beginning of a debt death spiral, one that Trump himself has ushered in rapidly by spending more money than the the nation has ever seen, totaling somewhere north of $7.8 trillion in his first term and on track to add $1.9 trillion for 2025. The attempt to save money embodied by the now defunct Department of Government Efficiency went absolutely nowhere. (Ringleader Elon Musk and staff are slated for depositions as of February 5, 2026.)

The national debt now stands at $38.56 trillion. Perhaps more important, the servicing of that debt, shown in the above graph, has reached epic proportions, totaling more than $1.2 trillion in interest payments in 2025. This death spiral can only be fixed by three things: reducing spending (failed), increasing taxes (Trump has done the opposite), or inflating away. Only the third option remains untested, and it would be decidedly in the president's interest, now that he has painted himself into a corner on the other two.

As the quote at the top of this section implies, Trump therefore does not have any problem with currency devaluation outside of the immediate harm it will do to the citizenry. Losing votes, in this case, may be considered worth the dual goals of combating Chinese economic warfare and inflating away the worsening crisis of out-of-control US debt. With tariffs ongoing, military spending ballooning, and government budget cuts not forthcoming, this is the emergent strategy. Far from "worrying" about the dollar, the president likely wants the dollar as low as the public can bear.

Affordability Goes Bust

"Trump Vows To Make the US Affordable Again, As Americans Feel the Pinch": President Donald Trump has told a campaign-style rally that consumer prices are falling "tremendously", as he seeks to allay voter anxiety about the cost of living in the US. - BBC (12/10/25)

American workers have one big complaint about their jobs: They don't get paid enough to keep up with the cost of living.

Even with cost-of-living adjustments or pay increases, 4 in 10 workers say their income has not kept up with their expenses, according to a new USA TODAY/SurveyMonkey Workforce Survey of more than 3,000 Americans. -USA Today (1/25/26)

When it comes to the confluence of geopolitical and domestic factors currently pushing and pulling at global governments, the United States is an example of what might be termed "too many things." It is not possible, it turns out, to combat Chinese economic tactics through tariffs, maintain a voting base through lowered cost of living, and give immense tax cuts to the rich, all simultaneously. Small wonder.

But in that confluence, a new pattern is emerging. While the US is in the trap in which it finds itself, allowing currency devaluation does serve a purpose. The ripple effects of doing this will always make any leader unpopular with the public, who lose the ability to cheaply go on vacation, afford basic goods, and trust their savings accounts. This is not good in the court of public opinion.

But a devalued currency is popular with manufacturers, promoting their ability to export goods. This combines with "shoot at everyone from the hip" tariff wars in very unpredictable ways, so it remains to be seen if exports will rise faster than the pre-existing trend lines. Angry allies make for poor customers, after all.

In the face of fighting off an unprecedented international goods-dumping experiment from China and a national debt crisis, there are advantages to engaging in a currency war. The real issue with doing so comes from the lessons of history with which this paper started. Today most resembles the 1930s - a period when the international monetary system was destroyed by major power currency wars that eventually went nowhere. The gold standard disappeared, valuations made no sense, and every country involved, in the end, was harmed.

It is easy to lambast institutions that don't currently serve you. It is far harder to undo the damage that can come from abandoning them. The Bretton Woods Agreement was designed for a reason: it served a purpose. And it was the result of a hard lesson learned.

For now, the US and China are already in a currency war. What remains to be seen is what the rest of the world will do in response. If all nations begin to pursue similar policies, a repeat of the wars of the Great Depression is likely. Perhaps the chaos that ensues will lead us to, yet again, an international institution or agreement designed to prevent such things.

Time, perhaps, really is a flat circle.

In the meantime, we will all have to deal with the consequences. With a rapidly devaluing US dollar, there is nowhere for money to go but out. Treasury sluggishness will surely continue. Gold, euros, yen, and perhaps cryptocurrencies that are more solid will eventually benefit. A few weeks ago, precious metals, euros, and the pound were all way up against the dollar. Lately, they are on a slight downtrend, with equities falling. Oil, denominated in USD, will always go up when the dollar weakens.

The problem for us all when too many things are in flux is that liquidity begins to slosh around the proverbial bathtub. The difficulty of predicting prices is magnified greatly when affordability declines, currency wars are afoot, and the dollar is down. Eroded wages leave American workers unable to keep up, hampering economic activity in the US and lowering the velocity of money.

The problem is simple to describe: eye-for-an-eye economics. Without the support of European allies' economic policies, it's hard to take on China. In an era of currency wars, tariffs, climate change, and new kinetic conflicts, the global economic pie will shrink. Safe-haven assets remain the wisest place to hide, and - at least for now - getting out of the dollar is the move. If a true global currency war comes to be, gold, land, and hard assets will be the only safe zones.

Whatever comes our way, as Bette Davis famously said in All About Eve:

Fasten your seatbelts. It's going to be a bumpy night.

Your comments are always welcome.

Sincerely,

Evan Anderson